Kenya's Coffee: Finding Higher Ground

Words and images by Charlie Denison (Originally published in Issue 7 of The Coffee Magazine, Autumn 2014)

The world’s most expensive commercial coffee comes from Kenya. Charles Denison explains why the coffees of Kenya are the most sought after on the continent and how the industry rests on the shoulders of around 700 000 small holder farmers. But is this prized coffee in danger?

I grew up, like most people reading this magazine, in a chicory and instant-coffee dominated country. I had a passion for caffeine back in those days, but slowly my passion and taste buds have been improving cup by cup and origin by origin into a passion for coffee. In a world where only 24% of coffee drunk is instant, South Africa has been traditionally stunted with regard to the type of coffee consumed. I spent my first couple of years as a budding “coffee aficionada” dodging burnt milk and bitter espressos looking for the rare diamonds in the rough. Back in 2006, this was a hard task, especially since this was before the advent of the AeroPress or the popularisation of the pour-over. I paid my dues, and learnt all about extraction, micro-textured milk, and latte-art.

It wasn’t until my first origin visit, to the lush coffee fields of Zambia, that I learnt how to really pronounce arabica (very different to the ara-beeeeca I had been saying garnering funny looks from the farmers)! It was on this trip that I first truly saw what coffee really was. And more importantly, what it meant. From here it was all downhill, down deep into the rabbit hole to the other side of coffee.

I had been studying in the snowy alps of Switzerland (where no coffee could ever possibly grow), and had been looking for an excuse to head back to the warm tropics of my home continent, when I devised a plan to write my Masters thesis on a subject I actually knew very little about at the time: coffee farming. I was lucky enough to get sponsorship from the African green bean specialists, Schluter Café, the Zambian government, and the Zambia Coffee Growers Association. My thesis focused on what was really close to my heart: the advancement of smallholder coffee farmers. It was a thesis I knew would not simply sit on a library shelf in Switzerland and get dusty, but actually have use in making a difference to the lives of the people who tirelessly grow our passion (coffee) and addiction (caffeine).

The coffee fields of Zambia were the start of many an origin visit, including Cuba, Madagascar, Zimbabwe, Malawi, and most recently Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. There aren’t many places on my travel bucket-list that don’t grow coffee! After my time in Zambia, I returned to the retail and roasting side of coffee in South Africa, but my heart always lay elsewhere. I knew my strengths and passion would have more impact and influence on the green side of coffee, and specifically at origin. I also had a feeling that I had not even explored more than the first tunnel of the deep and complex industry, and needed to return to those lush green fields, that mesmerising smell of the coffee blossom, and into the lives of the smallholder coffee farmers. I had to go back!

So the 4x4 was packed to the roof, with careful consideration made for the essentials, including of course an AeroPress (for those tediously long border crossings) and even a Nuova Simonelli Musica single group espresso machine and grinder! The long, bumpy road to Kenya began, 5500km in all! I was fortunate enough to get a job with ECOM trading, the worlds largest arabica traders, and one of the “big four” who together control most of the worlds coffee. Fortunately, big companies have big budgets, and this allows them - if the desire exists - to make a seriously positive impact on coffee farmers lives. ECOM has this desire, and I spent a large portion of my time in East Africa helping to understand and uplift the smallholder coffee farmers in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda.

Working with other big companies such as Nestle and Starbucks (who get a lot of flack in the industry as most big corporates do, but actually are making a difference due to their huge budgets and CSI requirements), I got to follow the path deeper, down into the depths of meaningful certifications and farmer upliftment through crop yield increases, and quality improvements.

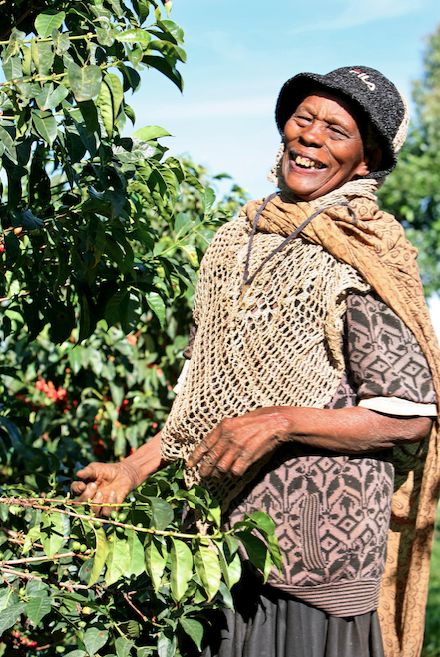

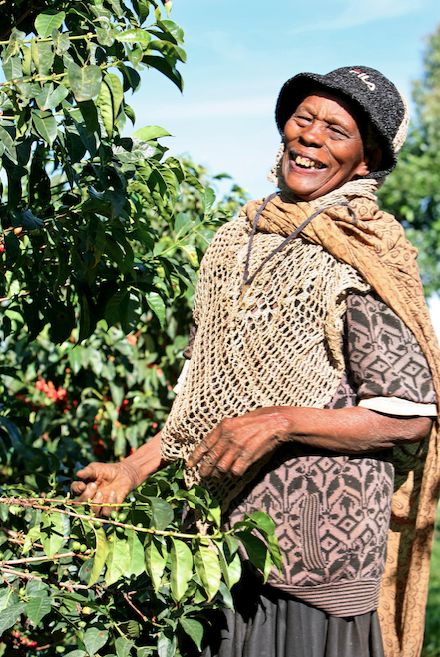

Africa’s coffee growing landscape is dominated by smallholder farmers, generally growing on less than two hectares of land. This land is often intercropped with other agricultural crops, such as the cash crops of bananas, maize and vegetables, as well as fodder and timber. In Kenya, the average coffee farmer has less than a hectare of land, growing on average about 300 coffee trees. There are over 700,000 registered coffee farmers in Kenya, growing a coffee so famous that it has become the world’s most expensive commercial coffee!

Kenya’s coffee system is not without criticism, but they tend to get a lot right, and if other origins could learn from and copy Kenya’s methods, I believe their quality would all improve. Kenya is the only country in the world where smallholders have consistently achieved better prices and quality than large estates. Smallholder coffee farmers in Kenya are grouped into cooperatives by region, with between 500-1000 farmers making up one wet-mill processing facility. Every day during harvesting season (of which there are two in Kenya due to two rainfall seasons – Main Crop harvested between September and December and Fly Crop harvested between April and June), the farmers will pick only the red, ripe cherries, and take them to the wet-mill on that same day. Here they are sorted further by colour and ripeness under the strict eye of the wet-mill manager, before being allowed into the pulper. I believe this one important step in quality control and strictness of cherry accepted into the mill is largely responsible for Kenya’s legendary quality.

After pulping, the coffee is sorted by density in water channels before washing and fermentation. Parchment coffee (still with the husk on) is then dried in the sun on “African drying tables” for days until around 12 percent moisture content is reached. The coffee is then stored in conditioning bins before being graded at the dry mill by density, size, and colour. From here 95% of Kenya’s coffee goes to the auction at the renowned Nairobi Coffee Exchange, which has been in operation since 1934. Each of the 50 or so registered buyers will receive a sample of every lot in advance to cup and grade, before heading to the auction house on a Tuesday for bidding on the 400 plus lots. This huge amount of coffee allowed me the opportunity of cupping around 200 cups per day!

The auction system is renowned for its transparency, and the cooperatives and the farmers receive a fair percent of the auction price. There are, however a lot of middlemen involved in the Kenyan system, and old habits die hard. The second window (buying direct and not through the auction) became law only a few years ago, and allows buyers now to make direct deals with the cooperatives and estates. This allows for a greater percentage to reach the farmer, while allowing for roasters to develop long-term relationships with the farmers and cooperatives.

Our work with the farmers in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda, focused mostly on increasing the farmer’s productivity in producing the coffee. There were two things that were out of our control (and the farmers control), and that was government regulations, and the New York “C” coffee price. During the middle of 2011, coffee hit its peak price, and was trading on the New York exchange at over $3 per pound, and today, at the time of writing, at less than $1,10 per pound. As the coffee price has dropped, so has the farmers income, by a massive margin, all due to factors far beyond the control of the Kenyan coffee farmer. So instead we looked where we could make the biggest difference in the immediate term, and that was with agronomy training, thereby improving yield and quality.

With ECOM, we worked together with a pyramid of trainers and promoter farmers to educate and assist over 83,000 smallholder coffee farmers. When the project started, the average farmer had a production as little as 1kg per tree. We would guarantee them a minimum of 3.5kg per tree, with the top farmers getting up to 10kgs! This was all achieved with simple agricultural practices, including mulching, composting, pruning, and application of necessary inputs, topped off with alternative income models of biodiesel, methane production, and intercropping. The second aspect we worked on was quality at the washing station wet-mill, as the better the quality, the higher the auction price is. On top of the quantity and quality improvements, we worked on getting farmers ready, and sponsoring them for certification programmes, including Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance, UTZ, and 4C’s, not only improving environmental and social aspects, but also achieving higher prices for the farmers.

The reason this became so important to me, and should be to all of us, is because of the declining interest in coffee farming, aging farmers, and diminishing farmlands. Kenya’s production has decreased from 129,000m2 in the late 1980’s to around 40,000m2 now. This is due to many coffee farms being re-zoned and utilised for property development (especially around Nairobi), a lack of interest amongst the younger generation to farm (the average age in some regions is over 60, with the youth preferring to live in the cities in increased urbanisation), and climate change (some regions are now unable to grow coffee any longer with the lower rainfall). On top of this, many farmers in the certain regions of Kenya are now pulling up their coffee to grow qhat (known as miraa in Kenya), a mild amphetamine stimulant drug, which is fetching far higher prices than coffee at the moment. If any of you have been lucky enough to taste a true Kenyan coffee, its brightness, complexity, clean cup, and uniqueness (just ask Craig Charity), you will understand how important it is to work with the farmers in realising fair profits for their hard work.

Country Profile: Kenya

Most expensive commercial coffee in the world

Known specifically for its bright acidity

Produce less than 1% of world supply

Two Harvesting seasons (main crop and fly crop)

40,000 mt (2012) down from 129,000mt in the late 80’s

70% Smallholder grown, 30% estate grown

700,000 Smallholder farmers between ½ hectare to 2 hectares

800 washing stations

Most coffee sold through Nairobi Coffee Exchange (auction) since 1934

Cultivars: SL28, SL34, Ruiru 11, Batian

African arabica Coffee Production & Facts (Africa = 12,5% world production):

1. Ethiopia (70% of Africa’s arabica)

2. Kenya (8%)

3. Tanzania

4. Uganda (top five robusta grower in world)

5. Rwanda

6. Burundi (coffee is 62% of Burundi’s total exports)

Source: Coffee: An Exporters Guide 2012